Lost and Found in Translation: How to Achieve Effective Cross-cultural Collaboration

Insights from working with an international team, Block Zero.

At Block Zero we pride ourselves in being an international studio with a diverse outlook. Our current team represents 7 countries spanning 5 continents – Sweden, Australia, France, South Africa, Estonia, Russia and Canada. This cultural diversity has given us a lot in terms of creativity, innovative approaches to challenges and, of course, precious moments like when our Australian colleague remarks, “She doesn’t come to work to **** (mess around) with spiders,” leaving everyone in the room puzzled. Undoubtedly our cultural diversity enriches our work, but there can be drawbacks, such as communication misunderstandings or inefficient collaboration.

International collaboration is a common and valuable part of any business today, and chances are high you have been in one yourself. And whether it is working with foreign colleagues, teams or clients, it is important to acknowledge that effective cross-cultural collaboration needs more time and effort, compared to collaborations within a singular cultural context.

In this post, I would like to share my personal observations of differences that arose at work, and how we could improve upon those situations according to The Culture Map: Breaking Through the Invisible Boundaries of Global Business by Erin Meyer. I hope this encourages you to reflect on your experiences of cross-cultural collaboration as well, and become more self-aware of your own preconceptions.

Why is Understanding Culture Important?

Most of us feel that our own perception of what is a normal and efficient way of working is the universal “standard” shared by all “normal” people. And if we encounter other people at work making “counter-productive” decisions, we easily become frustrated. However, instead of blaming other people for ineffectiveness, we can take this frustration as a sign that we might need to become more aware of what is a norm and what it means to be efficient at work for different people. And, as is often the case in international environments, the answer can be found in culture.

Of course, other characteristics like age, industry, gender and individual differences also come into play, and we all should always try to understand what is unique about each person. In fact, making broad social generalizations can be detrimental. However, I do also believe that this doesn’t takeaway the importance of learning about culture. If our team’s success at Block Zero, and perhaps your own business too, benefits from cultural diversity and the ability to work effectively with other teams from around the world, we must learn about each other’s cultural contexts as well as individual distinctions. Both aspects are crucial.

Why Am I Raising This Topic?

Coming to Sweden to work in an international studio from Russia made me question a lot of my standards and preconceptions about work, management and relationships within the team. It was not until I read the book The Culture Map: Breaking Through the Invisible Boundaries of Global Business by Erin Meyer that I started to understand the reasons behind these differences. I’ve found that it is very helpful to learn about my own culture to navigate this new world.

At this point, you might wonder, what are these differences she’s talking about? In the book, there are eight aspects where culture can manifest itself in a business context: communicating, evaluating, leading, deciding, trusting, disagreeing, scheduling and persuading.

What is important here is not the absolute position of either culture on the scale, but rather how they are positioned in relation to each other. Naturally, my own perspective has influenced these reflections: it is the position of my own culture that shapes my perception of others. Now, let’s see how this scale works in practice in the following workplace examples.

Differences in Reasoning Styles

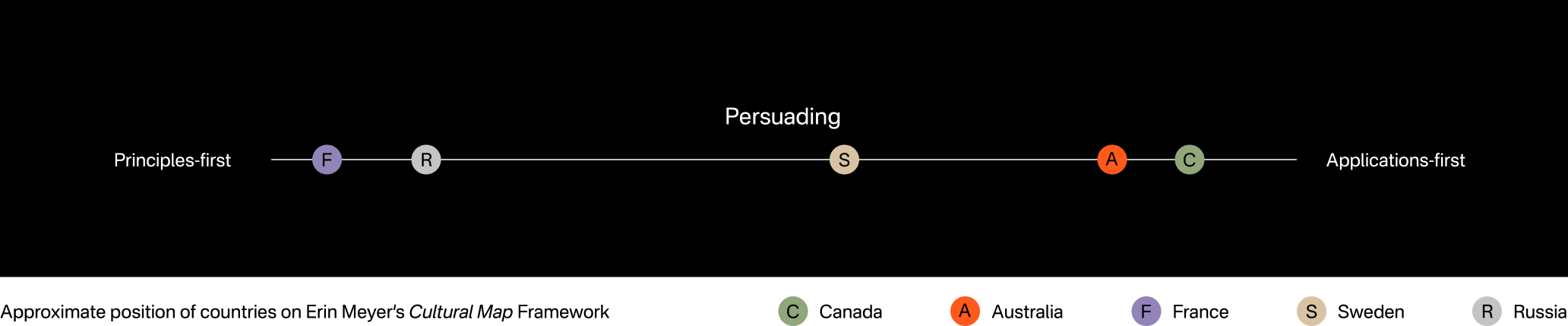

When we decide how to talk about our work, both internally or in the way we present case studies on our website, there are usually two approaches that clash.

Some of us believe it is important to start presenting the work by highlighting the design methodologies we took to solve the challenge, and gradually reveal the steps we took to achieve the final practical outcome. While others point out that by doing so, we lose the attention of our readers and listeners, and therefore we should start with, and focus more, on the practical outcomes to communicate our work in the most effective way.

Meyer provides a profound theory behind these two approaches: the way different societies analyze the world and “present” their understanding to each other depends on the philosophers who influenced intellectual life and science in their country (Descartes’ deductive reasoning or Aristotle’s inductive reasoning). This, in turn, defines how we learn in school and how we behave as adults at work.

For example, in school in my home country, we were taught to first comprehend the general theory and concepts before arriving at practical examples (deductive reasoning). This logical pattern informs what I think will be more natural, hence a more influential way of presenting something to other people.

However, another approach makes more sense if you were taught to begin with a fact and then add background theory to explain it (inductive reasoning). In the business context of these countries, it is important to get to the point early on to be persuasive.

The Culture Map Recommends

Of course, we should always take into account to whom we are presenting and where they come from. Given our international team and the diverse audience we want to talk to, it is good to keep a mix of these approaches. Meyer recommends alternating between theoretical concepts and practical outcomes. She posits that it is good to start with the latter to grab the attention of those more inclined toward real-world applications – the other group will enjoy them also. However, people interested in theoretical aspects might start raising questions, and it is important to answer them thoroughly, even though it might get boring to the practical listeners, before coming back to the practical examples. This way you will re-capture the attention of one group, without sacrificing the respect of another group.

Perception of Time: Linear Versus Flexible Approach

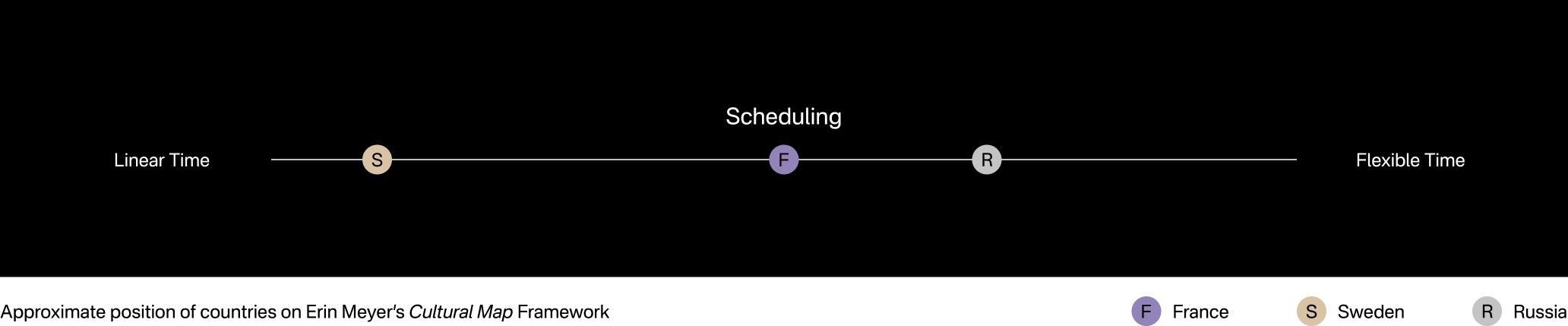

During my first months of working in Sweden, I encountered three bewildering and seemingly unrelated things.

- Swedes can plan things months in advance.

- In one of my first internal meetings, a colleague didn’t show up within the first two minutes, and the rest decided it was time to start pinging him.

- It is unacceptable to cut in line, even accidentally.

While reading The Culture Map, I learned about the Scheduling scale and differing attitudes toward time, which explained to me why I found these examples above noteworthy. In countries from one side of the scale, including Sweden, time is perceived as linear: everything happens in linear sequence, one thing at a time, everything is managed in proper order, including people who are waiting in line. The focus is on the deadline, sticking to the schedule and prioritizing organization over flexibility.

On the opposite end of the scale are countries with a flexible approach to time, where everything is handled in a dynamic way. They adjust as opportunities present themselves, and value adaptability more than strict organization.

Where a country is positioned on the scale is partially dependent on how fixed and reliable versus dynamic and unpredictable daily life in a given country is. In the society where I grew up, life revolved around constant change, the government could suddenly introduce new regulations, and the currency was never stable. In this environment, flexibility, ease and the speed with which you react to changes is what defines effectiveness and productivity. Planning ahead is fine, but it is only realistic if the time frame is a week or so.

The Culture Map Recommends

An amusing thing about this scale is how people from either end perceive those on the opposite side as inefficient and assume they have stressful lives. However, both approaches can be effective. Meyer suggests then that in international collaborations, it is therefore important to decide, as a group, on your own team culture. Determining what kind of balance between flexibility or structure is expected from everybody helps reduce everyone’s stress levels and improves productivity.

What Makes a Good Communicator?

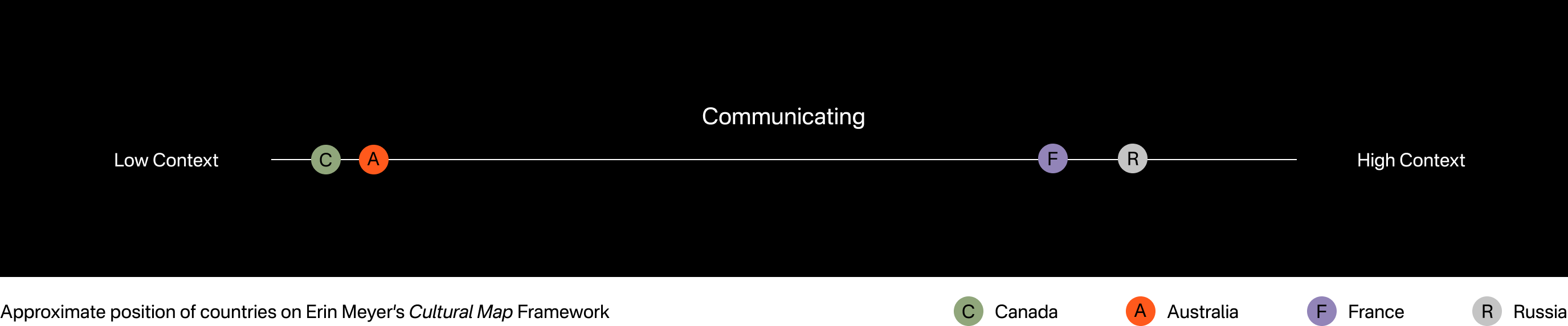

I will share one more example that concerns differences in communication styles: “high context” versus “low context”. Where I come from, a good communicator is someone who can pass the message concisely, without stating the obvious. Through contextual clues you can always understand a lot without it being said explicitly. In Meyer’s book, this style of communication is referred to as a “high context”. And on the other end of the Communication scale are “low context” cultures, where good communication is precise, simple and direct.

So, when I interact with my colleagues, I tend to read between the lines more than reading the actual lines, because I hold them to a high standard to what a good communicator is in my understanding. I was once asked to help out with the slide deck – it needed visual polishing. When I asked how much time there was for this task, my Canadian boss, who comes from a “low context” culture, replied: “…if it would take you less than an hour…, then that is what we should do…”. And the deadline was “Today.”

My brain, trained to be obedient to orders from above, and reacting to the sharp “period” at the end of the sentence, interpreted it as: “My boss dares me to do this in one hour, if I’m not useless and slow. And if the deadline is today, then the countdown starts asap, because most probably there is a meeting he needs it for”.

For the following hour, I frantically moved pixels, drowning in sweat from the adrenaline rush. I managed to complete it within the time frame, and hit send. However, later in the day when I talked with my boss, I understood that there wasn’t any meeting happening that day at all. I had read into a context that wasn’t there.

After reading the book, I realized that if there was a rush, my boss, as a Canadian, would explicitly state this. Like any other good communicator from a “low context” culture would, where messages are expressed and understood at face value.

Beyond that, a scenario where someone in top positions within the hierarchy would issue commands to the rest of the team in such an autocratic fashion wouldn’t even happen in Sweden. Because, at least compared to where I come from, there’s no rigid hierarchy in the workplace here at all.

The Culture Map Recommends

To prevent such misunderstandings, The Culture Map suggests using a “low context” communication style within international teams. For those, like myself, coming from a “high context” culture, the key takeaway is to be mindful of expecting others to grasp implicit messages and instead make an effort to express thoughts more directly. It’s sometimes beneficial to avoid excessive politeness, as the message can be perceived as ambiguous and uncertain.

On the other hand, if you come from a “low context” culture and are interacting with a higher-context one, Meyer suggests practicing your listening skills, asking open-ended questions for clarification, and refraining from assuming that the other person is unable to communicate explicitly.

Typically, both parties are communicating in the style they are accustomed to, without intending to be confusing, offensive or misleading. Usually providing a brief explanation of your behavior can make all the difference in how you are perceived by others.

How Have We Managed So Far?

The examples from above are far from being the only ones I have encountered. I am just trying to finish writing this on time to meet my Swedish deadline, combine theory and practical examples in this text, and of course be as direct as I can, as Erin Meyer prescribed. Thank you for sticking with me until now!

You might be wondering how I managed to work so far, given so much potential for confusion? I have the same question.

But jokes aside, I think I have managed because the Block Zero team is doing quite well when it comes to managing cross-cultural collaboration. It is only due to the established transparent and safe team culture that makes it possible to uncover so many insights and improvement opportunities. We put theory to action every other week by conducting a session that we use to run team development and creativity workshops. We compliment these workshops with 1-1 sessions with the management to raise more personal topics. This is how we make sure everyone is heard, appreciated and gets the support they need.

Where Do You Fit on the Cultural Map?

While this post shows how my experiences in an international design studio align with Erin Meyer’s framework, I encourage you to read the book and form your own interpretations, which will be equally valid as mine.

After all, the book is about recognizing how our cultural background shapes our perceptions, and advocates for transparent communication, perhaps with a touch of humor and humility, to help us build strong, efficient and creative teams.